Resurrecting a 13-year-old high school project: the BSoD lock screen

One day, during the winter break away from work, I was reminded of this ancient program I built in high school—a Blue Screen of Death (henceforth BSoD) simulator. It really has been a while since I’ve covered coding topics on this blog, so I thought it might be time to dig up the program and resurrect it.

But you might ask the very natural question: why did I write such a program? For that, I blame the school. You see, I had to deal with school computers a lot back in the day, not being one of those “cool kids” who brought their own laptops to school. Naturally, the school computers ran Windows XP1. For some reason, the school administrators decided to deploy group policy to deny screen locking.

This posed a conundrum: if I had to step away from the computer—like say, answering the call of nature—I was confronted with two deeply uncomfortable choices:

- Save all my work, close all applications, and log out, then wait forever to log back in on those slow computers, while hoping that no one else took the fastest one of the bunch2; or

- Leave the computer unattended, and if someone does something sketchy as a prank, I’d be the one in trouble.

One day, I saw a school computer stuck with a BSoD, and no one ever touched it, and that gave me an idea: what if I wrote my own custom “lock screen” program that masqueraded as a BSoD? And thus was the program born.

What did it do?

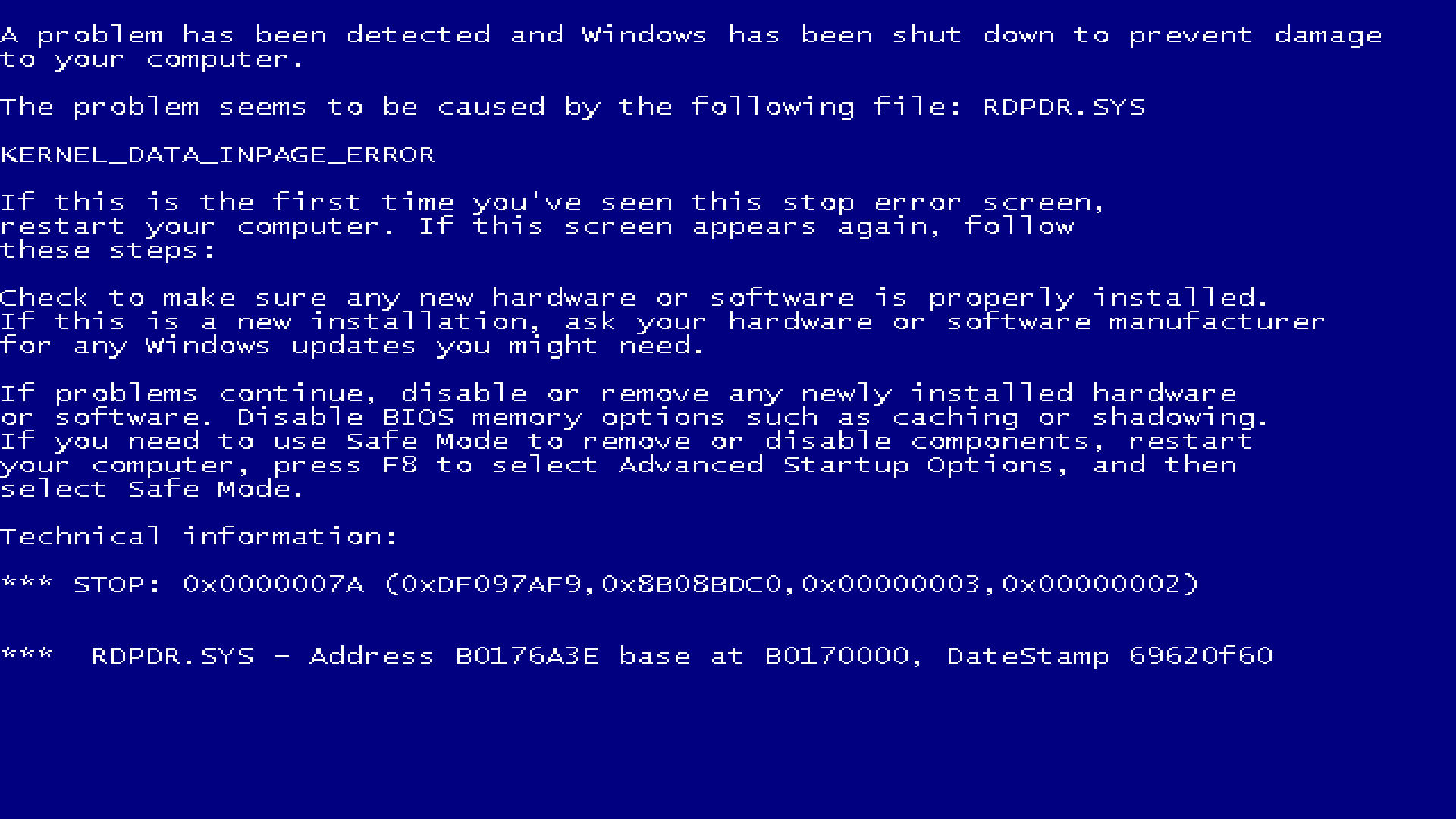

The program obviously needed to display a BSoD in full screen mode. The first

iteration of the program simply loaded the PNG downloaded from Wikipedia,

specifically this picture. It was very easy to tell after a while

that the screen was fake due to it looking the same every time. It really

doesn’t help that the current Unix time3 in hexadecimal is shown at the

very end. For example, the Wikipedia picture says DateStamp 3d6dd67c, which is

1,030,608,508 seconds after the Unix epoch, or 2002-08-29 08:08:28 UTC. Given

that in the 2010s, no timestamp should start with 3 in hexadecimal, this

easily gave the game away to those who understand.

So naturally, the program had to render an actual BSoD, generating random but

believable values for every field, using the current time in the DateStamp

field.

It also needed several features to be effective as a lock screen, like completely blocking access to the system while it’s running, or what’s the point? So it had to:

- be a topmost window in addition to being full screen, blocking all regular windows from view;

- prevent random system popups, such as the built-in sticky keys prompt, which inevitably showed up when testers spammed the keyboard;

- prevent the task manager from being launched to kill the program;

- prevent the program from being killed some other way;

- block most keyloggers through the use of a “secure desktop”, since I’d be typing in a password;

- prevent someone from logging me out without my authorization; and

- prevent the system from being shut down (except by pulling the plug).

The exact way these functionalities are accomplished will be described later, when we dive into the implementation details.

What it can’t do is intercept Ctrl+Alt+Delete,

which is handled by winlogon.exe with no exceptions. Microsoft specifically

designed it as a “secure attention sequence” to help the user confirm that they

are typing their password into the real login screen and not a fake program

phishing for the password. On school computers, pressing

Ctrl+Alt+Delete shows a screen asking the user

for various options, which unfortunately could not be blocked and looked

something like this:

(Naturally, the “Lock Computer” option was greyed out on the actual school computers, or I wouldn’t have to write this program.)

Still, it did the best it could, and surprisingly few people know about the intricacies of Ctrl+Alt+Delete…

The development environment

Programs are the product of their environment, and my BSoD program is no exception. For something that will need to call a lot of Windows API calls directly, any higher-level language like Python or Java is automatically out. The obvious candidates were C and C++.

I wanted to be able to develop this program on a school computer, in case I found a bug that I wanted to fix immediately without waiting to go home, so it had to work on a tiny toolchain that I could bring to school and not take up too much space. For this purpose, I chose the Microsoft Visual C++ 6.0 toolchain (henceforth VC6) from 19984, which, after debloating, compressed down to around 9 MiB with 7-Zip.

In this vein, I tried to make the final executable as lightweight as possible,

so C++ was automatically out. That meant I had to write this program in C, and

since VC6 pre-dated the C99 standard, the only acceptable form of C was C89.

This had several annoying quirks, such as requiring all variable declarations to

be hoisted manually to the top of every scope, no exceptions, or requiring the

loop variable of a for-loop to be declared separately, but was otherwise

reasonably similar to modern C.

Since the compiler predated 64-bit Windows, and the school computers were exclusively 32-bit anyway, no attempt was made to support compiling in 64-bit mode. The program would run fine on 64-bit Windows anyway through WoW64.

VC6 also had the advantage of supporting dynamic linking for a smaller

executable size without requiring a runtime redistributable to be installed,

which often isn’t the case for newer versions of Visual C++, and whether each

school computer had each redistributable was completely random. However, when

dynamically linking the C runtime on VC6, it simply used msvcrt.dll, which is

part of the operating system. It’s quite understandable why Microsoft gave up on

this approach, since it made it impossible to add newer features without causing

“DLL hell” or application compatibility issues, but still… Naturally, it was

possible to statically link the C library, but that added to the executable

size.

Although in the end, none of the C library linking stuff ended up mattering, because I decided to ditch the C library to achieve the minimum possible executable size…

Raw Windows API programming

Most people who have written a Windows GUI program would know that the program entry point is:

int WinMain(HINSTANCE hInstance, HINSTANCE hPrevInstance, LPSTR lpCmdLine, int nShowCmd);

However, this is not strictly true. As Raymond pointed out, this is actually a function provided by the C runtime library to replicate the behaviour of 16-bit Windows, and the actual real entrypoint for the program is

DWORD APIENTRY RawEntryPoint(void);

Partly inspired by that blog post, this program did the insane thing of ditching

the C library and programming directly to RawEntryPoint. This meant that no C

library function could be used at all, only Windows APIs. Due to choosing C

instead of C++, this was actually possible to accomplish, as I would otherwise

have to avoid most C++ features like the plague due to the runtime being

implicitly used in most of them.

On newer compilers, several security features, such as guards against stack buffer overflows, had to be turned off, as those require runtime support. Fortunately, VC6 didn’t have those features anyway…

In retrospect, this was totally not worth it, but that’s how the program was constructed. Clearly, I had too much time in high school…

Seeing the program in action

You can download the latest source code from GitHub and compile it yourself, if you have a copy of Visual C++ lying around. Most versions should work, but for the authentic experience, you should use VC6. A VC6-compiled binary is available on my Jenkins instance5.

It should look like this, with a random driver and error code selected:

To exit, hold down Alt and press the following keys in sequence: F2, F4, F6, F8, 1, 3, 5, 7. Then, press Ctrl+Alt+Shift+Delete.

Enter the password quantum5.ca to exit.

Lessons learned

Given that 13 years have gone by since the program was made, it’s inevitable that I would probably have done things differently now compared to then.

Code-wise, I didn’t have to make too many changes to satisfy my current self. The biggest issue was using funny magic numbers instead of defining them as proper constants, but that was easily rectified. I would probably not have ditched the C library writing this now, but it really wasn’t that big of a burden for this application, as you shall see.

The real lesson lies in the non-coding portion, and underscores how writing code is probably the easiest part of software development. There are many things I would have done differently:

- Using source control. Apparently, my younger self didn’t bother with any kind of source control and just emailed the source code around in plain text. This made it quite difficult to determine the canonical latest version of this program. It is entirely possible that a version with more fixes here got lost over the years. These days, it’s completely unimaginable for me to not use Git to manage everything.

- Using a proper build system, even if it’s just Makefiles. Apparently, my

younger self just had a command line to compile the program written down

separately, which depended on a bunch of generated files that were not

obvious how to regenerate, such as a compiled

.resfile. This required a bit of forensic work to reconstruct the.rcfile so I could compile it again. Even worse, the flags to compile the source under VC6 were written down in a completely different place compared to newer versions of the compiler… It really didn’t help that the source code was sent around as text in emails, without any supporting files. In the modernized Git repo, there is a proper Makefile, and a separate one for legacy VC6. Both of these will build the program completely from scratch, instead of relying on distributing intermediate files. - Using continuous integration. Apparently, my younger self had a ton of slightly different executables floating around in a directory somewhere, and it’s not clear which one is the “good” one. This was clearly insane. The modernized version has GitHub Actions set up to build every commit to ensure the repository successfully compiles under modern compilers, without dependency on any local, uncommitted files. I also have Jenkins set up specifically with VC6 to generate builds with the authentic original toolchain for every commit, ensuring that the latest executable is always available.

- Using an autoformatter, like

clang-format. My younger self decided to manually format all the code, resulting in a coding style that’s not quite consistent. While it doesn’t matter as much for a single-person project like this, having an autoformatter is essential in larger projects involving multiple people to avoid lots of different styles mixing and blending together. The current GitHub version has a.clang-formatfile defining the expected style.

Nevertheless, I am pleasantly surprised by my younger self at close to half my current age!

Annotated source code

Before we dive in, it’s important to keep in mind that the program is structured to have a bunch of macros that could be defined at compile time to control the behaviour:

-

NOAUTOKILL, which disables the automatic exiting after 50 seconds logic. This is invaluable when developing; and -

NOTASKMGR, which disables the task manager. The way it does so is kinda sketchy, so this gives an opt-out.

Without further ado, let’s look at the source code, which canonically resides on GitHub.

Headers

#define _WIN32_WINNT 0x0500

#define WINVER 0x0500

#include <windows.h>

First, we define version macros. In this case, we ask windows.h to make

available all functions available in Windows 2000, which has everything we

needed.

#include <aclapi.h>

#include <shlwapi.h>

We then include two more Windows header files, one for ACL operations, and the

other for the wnsprintf function. This is an obscure sprintf variant that I

would never normally use, except sprintf isn’t available due to libc being

ditched. Borrowing the version from shlwapi.dll was the natural solution.

Macros

#define ARRAY_SIZE(x) (sizeof(x) / sizeof *(x))

We define this handy ARRAY_SIZE macro so we can just pass in an array and

compute its size as a constant. The way this works is by calling sizeof on the

whole array to get its size in bytes, then calling sizeof to get the size of

the first element of the array in bytes, and dividing. sizeof *(x) yields the

size of the first element because arrays decay to the pointer to the first

element in most contexts, including dereferencing, so *(x) yields the first

element.

This macro will be broken if the argument isn’t an actual C array. If I cared more, I would make a better version that errors out when something else is passed in, but oh well.

#define WM_ENFORCE_FOCUS (WM_APP + 0)

#define TM_DISPLAY 0xBEEF

#define TM_AUTOKILL 0xDEAD

#define TM_FORCEDESK 0xFAC

#define AUTOKILL_TIMEOUT 50000

#define DISPLAY_DELAY 1000

#define FORCE_INTERVAL 1000

#define HDLG_MSGBOX ((HWND) 0xDEADBEEF)

#define IDC_EDIT1 1024

We then define a bunch of constants, including a window message, a bunch of

timer messages, a bunch of time intervals, and some other values. Everything

other than WM_ENFORCE_FOCUS manifested as magic numbers in the code. I’ve

preserved the original values, but gave them proper names.

IDC_EDIT1 is notably duplicated in bsod.rc, the resource file. If I had more

than one constant, I would have defined a header and included it in both

bsod.rc and bsod.c.

Compatibility

#if defined(_MSC_VER) && _MSC_VER <= 1200

#define wnsprintf wnsprintfA

int wnsprintfA(PSTR pszDest, int cchDest, PCSTR pszFmt, ...);

typedef unsigned char *RPC_CSTR;

#endif

To ensure it builds on the ancient VC6 with its outdated Windows SDK headers, we

define the prototype of wnsprintf, which is actually wnsprintfA in the DLL

due to it being the non-Unicode version. Windows headers normally define a macro

to replace the name with either the A or W version, depending on whether the

UNICODE macro is defined.

We also define the RPC_CSTR type, since we’ll be using an RPC function later,

and that type is somehow missing in VC6.

typedef BOOL(WINAPI *LPFN_SHUTDOWNBLOCKREASONCREATE)(HWND, LPCWSTR);

typedef BOOL(WINAPI *LPFN_SHUTDOWNBLOCKREASONDESTROY)(HWND);

This defines the function pointer types for ShutdownBlockReasonCreate and

ShutdownBlockReasonDestroy functions introduced in Windows Vista, in

anticipation of the school upgrading to Windows 7, which did happen eventually.

These will be needed to actually block shutdown on newer versions of Windows.

Function prototypes

LRESULT CALLBACK WndProc(HWND, UINT, WPARAM, LPARAM);

INT_PTR CALLBACK DlgProc(HWND, UINT, WPARAM, LPARAM);

LRESULT CALLBACK LowLevelKeyboardProc(int, WPARAM, LPARAM);

LRESULT CALLBACK LowLevelMouseProc(int, WPARAM, LPARAM);

We now define a bunch of function prototypes.

Constants

#define PASSWORD_LENGTH (sizeof(szRealPassword) - 1)

const char szRealPassword[] = {0x54, 0x50, 0x44, 0x4b, 0x51, 0x50,

0x48, 0x10, 0xb, 0x46, 0x44, 0x00};

const char szClassName[] = "BlueScreenOfDeath";

This defines two constants, one for the encoded password, and one for the window class name.

The password is quantum5.ca, encoded by XORing with the number 37. I don’t

remember why it was chosen, other than perhaps because it’s a prime number.

Variables

We now declare a bunch of global variables:

HINSTANCE hInst;

HWND hwnd; // Main window

HWND scwnd; // Static bitmap control

HWND hdlg; // Password popup

HACCEL hAccel;

HHOOK hhkKeyboard, hhkMouse;

HDESK hOldDesk, hNewDesk;

char szDeskName[40];

LPFN_SHUTDOWNBLOCKREASONCREATE fShutdownBlockReasonCreate;

LPFN_SHUTDOWNBLOCKREASONDESTROY fShutdownBlockReasonDestroy;

Note that using global variables like this is not recommended, but in this case, there’s no way one instance of this program will ever show more than one window, so whatever.

hInst exists solely because a bunch of Windows APIs ask for HINSTANCE due to

16-bit compatibilty reasons. Normally, you’d save the hInstance passed to

WinMain, but we don’t have that. You’ll see how we calculate it later.

The HWND variables are self-explanatory.

The HACCEL is for storing a handle to the accelerators, and we will be using

keyboard accelerator tables instead of implementing complex parsing logic for

keystrokes.

HHOOK variables are used to create low-level keyboard and mouse hooks.

HDESK variables are used to store the handle to the original desktop and a new

“secure desktop.” szDeskName stores the name of the secure desktop.

We also define variables to store the pointers to ShutdownBlockReasonCreate

and ShutdownBlockReasonDestroy functions, if they exist.

#ifdef NOTASKMGR

HKEY hSystemPolicy;

#endif

If the task manager is to be disabled, we define an HKEY to store a handle to

a certain registry key.

Keyboard accelerator table

ACCEL accel[] = {

{FALT | FVIRTKEY, '1', 0xBE00},

{FALT | FVIRTKEY, '3', 0xBE01},

{FALT | FVIRTKEY, '5', 0xBE02},

{FALT | FVIRTKEY, '7', 0xBE03},

{FALT | FVIRTKEY, VK_F2, 0xBE04},

{FALT | FVIRTKEY, VK_F4, 0xBE05},

{FALT | FVIRTKEY, VK_F6, 0xBE06},

{FALT | FVIRTKEY, VK_F8, 0xBE07},

{FALT | FCONTROL | FSHIFT | FVIRTKEY, VK_DELETE, 0xDEAD},

};

BOOL bAccel[ARRAY_SIZE(accel) - 1];

Here, we define a keyboard accelerator table, uncreatively called accel. This

will eventually be passed to CreateAcceleratorTable. We define 8 shortcut keys

to be pressed, generating WM_COMMAND messages with codes 0xBE00 to 0xBE07

in wParam. These can be triggered by holding down Alt and then

pressing the 1, 3, 5, 7,

F2, F4, F6, and F8 keys. bAccel

tracks whether any of these keys were pressed.

Finally, there’s a shortcut for

Ctrl+Alt+Shift+Delete, which

triggers a WM_COMMAND with 0xDEAD, that signals the program to trigger the

exit routine.

Helper functions

void GenerateUUID(LPSTR szUuid) {

UUID bUuid;

RPC_CSTR rstrUUID;

UuidCreate(&bUuid);

UuidToString(&bUuid, &rstrUUID);

lstrcpy(szUuid, (LPCSTR) rstrUUID);

RpcStringFree(&rstrUUID);

}

This function generates a UUID, which will be used to create a random and

guaranteed-to-be-unique name for a secure desktop. It uses a bunch of functions

from rpcrt4.dll, like UuidCreate and UuidToString, to generate the UUID,

and we use lstrcpy to copy it into the buffer passed in, before freeing the

weird RPC_CSTR. Note that lstrcpy from kernel32.dll is used because we

can’t use strcpy in the C library.

int UnixTime() {

union {

__int64 scalar;

FILETIME ft;

} time;

GetSystemTimeAsFileTime(&time.ft);

return (int) ((time.scalar - 116444736000000000i64) / 10000000i64);

}

This is effectively a reimplementation of the time function from the C

standard library, which we can’t use. So instead, we use

GetSystemTimeAsFileTime, which returns the current time as a 64-bit integer,

divided into low and high parts as 32-bit DWORDs in the FILETIME structure.

To make it easily interpretable, we convert it to __int64—Microsoft’s

extension type for 64-bit integer in the days before long long is properly

supported—through a union, which is the safe way to ensure it’s properly

aligned.

Note that FILETIME is defined as measuring the time in 100 ns intervals

since midnight UTC on January 1, 1601. To convert this to Unix time, we need to

subtract 116,444,736,000,000,000 such intervals, i.e. 11.6 billion seconds, to

make the zero point the Unix epoch, and then divide by 10 million to convert to

seconds.

Note that this implementation technically uses the Microsoft Visual C++ library

function _alldiv to perform the division. However, that file does not

introduce any further dependencies on the C library, most notably the

initialization code, which is the main source of bloat. However, if you really

hate the C library, the following alternative implementation in x86 assembly

will avoid it:

__declspec(naked) int UnixTime(void) {

__asm {

sub esp, 8

push esp

call dword ptr GetSystemTimeAsFileTime

pop eax

pop edx

sub eax, 3577643008

sbb edx, 27111902

mov ecx, 10000000

idiv ecx

ret

}

}

But I see no need to make the code unreadable for the exact same executable size… Anyways, let’s go on:

int Random() {

static int seed = 0;

if (!seed)

seed = UnixTime();

seed = 1103515245 * seed + 12345;

seed &= 0x7FFFFFFF;

return seed;

}

We then use this crappy random number generator that uses the current Unix time as a seed. This isn’t going to win any awards or be suitable for cryptographic use, but it’s good enough for this program.

For those curious, this implementation is a linear congruential

generator, specifically with the parameters used in glibc, with the

output capped to be positive through bitwise AND with 0x7FFFFFFF.

Protection functions

And then we have a bunch of functions to make sure the program doesn’t get killed…

#ifdef NOTASKMGR

void DisableTaskManager(void) {

DWORD dwOne = 1;

if (hSystemPolicy)

RegSetValueEx(hSystemPolicy, "DisableTaskMgr", 0, REG_DWORD, (LPBYTE) &dwOne,

sizeof(DWORD));

}

void EnableTaskManager(void) {

DWORD dwZero = 0;

if (hSystemPolicy)

RegSetValueEx(hSystemPolicy, "DisableTaskMgr", 0, REG_DWORD, (LPBYTE) &dwZero,

sizeof(DWORD));

}

#endif

These functions disable and enable the task manager by setting a registry key

that would normally be controlled by group policy. Specifically, it sets a value

named DisableTaskMgr under the key in hSystemPolicy, which will be opened to

HKEY_CURRENT_USER\Software\Microsoft\Windows\CurrentVersion\Policies\System.

This is only active if the NOTASKMGR macro is defined.

DWORD ProtectProcess(void) {

ACL acl;

if (!InitializeAcl(&acl, sizeof acl, ACL_REVISION))

return GetLastError();

return SetSecurityInfo(GetCurrentProcess(), SE_KERNEL_OBJECT, DACL_SECURITY_INFORMATION, NULL,

NULL, &acl, NULL);

}

This function creates a blank ACL and sets it on the current process object. Since a blank ACL does not grant any permissions, it means that no one has the permission to perform any operations on this process, for “nefarious” things such as terminating it.

Fun fact: I learned this trick from this crapware that the school had

installed on the computers. I had a batch file that killed all the startup

programs to squeeze out every drop of performance on the ancient school

computers, and that one program couldn’t be killed. Naturally, I studied how it

worked, and it did so by updating the ACL to deny everyone PROCESS_TERMINATE,

i.e. the ability to call TerminateProcess on it. It had a fatal flaw: it

didn’t stop someone from calling CreateRemoteThread on the process. Naturally,

I wrote a helper program that created a remote thread in the crapware that ran

ExitProcess, and lo and behold, the crapware was successfully killed.

Since I am using a blank ACL here, it uses a lot less code than updating the ACL

as used by that crapware, and there’s the added bonus that it denies all sketchy

operations, including CreateRemoteThread and any other debugging operations…

Also note that ACLs are supposed to be variable length and heap-allocated, with

stuff coming after the ACL structure in the same block of memory, but the

degenerate case of the empty ACL fits on the stack just fine.

STICKYKEYS StartupStickyKeys = {sizeof(STICKYKEYS), 0};

TOGGLEKEYS StartupToggleKeys = {sizeof(TOGGLEKEYS), 0};

FILTERKEYS StartupFilterKeys = {sizeof(FILTERKEYS), 0};

void AllowAccessibilityShortcutKeys(BOOL bAllowKeys) {

if (bAllowKeys) {

SystemParametersInfo(SPI_SETSTICKYKEYS, sizeof(STICKYKEYS), &StartupStickyKeys, 0);

SystemParametersInfo(SPI_SETTOGGLEKEYS, sizeof(TOGGLEKEYS), &StartupToggleKeys, 0);

SystemParametersInfo(SPI_SETFILTERKEYS, sizeof(FILTERKEYS), &StartupFilterKeys, 0);

} else {

STICKYKEYS skOff = StartupStickyKeys;

TOGGLEKEYS tkOff = StartupToggleKeys;

FILTERKEYS fkOff = StartupFilterKeys;

if ((skOff.dwFlags & SKF_STICKYKEYSON) == 0) {

skOff.dwFlags &= ~SKF_HOTKEYACTIVE;

skOff.dwFlags &= ~SKF_CONFIRMHOTKEY;

SystemParametersInfo(SPI_SETSTICKYKEYS, sizeof(STICKYKEYS), &skOff, 0);

}

if ((tkOff.dwFlags & TKF_TOGGLEKEYSON) == 0) {

tkOff.dwFlags &= ~TKF_HOTKEYACTIVE;

tkOff.dwFlags &= ~TKF_CONFIRMHOTKEY;

SystemParametersInfo(SPI_SETTOGGLEKEYS, sizeof(TOGGLEKEYS), &tkOff, 0);

}

if ((fkOff.dwFlags & FKF_FILTERKEYSON) == 0) {

fkOff.dwFlags &= ~FKF_HOTKEYACTIVE;

fkOff.dwFlags &= ~FKF_CONFIRMHOTKEY;

SystemParametersInfo(SPI_SETFILTERKEYS, sizeof(FILTERKEYS), &fkOff, 0);

}

}

}

This is the helper function that toggles the Windows accessibility shortcuts,

specifically for sticky keys, toggle keys, and filter keys. We define three

structures to store the state of each, which will be populated on startup. The

helper function, when told to allow, will set those three back to the original

state with SystemParametersInfo. When told to disallow, it will remove the

bits for the keyboard shortcut and the confirmation dialogue from the flags for

each.

Generating the blue screen

LPSTR bsod1 = "\r\n\

A problem has been detected and Windows has been shut down to prevent damage\r\n\

to your computer.\r\n\

\r\n\

The problem seems to be caused by the following file: ";

LPSTR bsod2 = "\r\n\r\n";

LPSTR bsod3 = "\r\n\

\r\n\

If this is the first time you've seen this stop error screen,\r\n\

restart your computer. If this screen appears again, follow\r\n\

these steps:\r\n\

\r\n\

Check to make sure any new hardware or software is properly installed.\r\n\

If this is a new installation, ask your hardware or software manufacturer\r\n\

for any Windows updates you might need.\r\n\

\r\n\

If problems continue, disable or remove any newly installed hardware\r\n\

or software. Disable BIOS memory options such as caching or shadowing.\r\n\

If you need to use Safe Mode to remove or disable components, restart\r\n\

your computer, press F8 to select Advanced Startup Options, and then\r\n\

select Safe Mode.\r\n\

\r\n\

Technical information:\r\n\

\r\n";

LPSTR bsod4 = "*** STOP: 0x%08X (0x%08X,0x%08X,0x%08X,0x%08X)";

LPSTR bsod5 = "\r\n\r\n\r\n*** ";

LPSTR bsod6 = "%s - Address %08X base at %08X, DateStamp %08x";

First, we have a bunch of string fragments that comprise the text shown on the

blue screen. These are divided into six chunks, and bsod4 and bsod6 are

actually printf-style format strings.

LPSTR lpBadDrivers[] = {

"HTTP.SYS", "SPCMDCON.SYS", "NTFS.SYS", "ACPI.SYS", "AMDK8.SYS", "ATI2MTAG.SYS",

"CDROM.SYS", "BEEP.SYS", "BOWSER.SYS", "EVBDX.SYS", "TCPIP.SYS", "RDPDR.SYS",

};

We then have a bunch of system drivers that could be blamed for the crash. I am not sure why most of these were selected in particular, but I think:

-

ATI2MTAG.SYSwas selected because the school computers had ATI6 graphics cards, and the display driver often crashed; -

BEEP.SYSwas selected because I had code in MusicKeyboard that directly interfaced with it; and -

BOWSER.SYSwas selected because it had a weird name that was not a typo.

typedef struct {

LPSTR name;

DWORD code;

} BUG_CHECK_CODE;

BUG_CHECK_CODE lpErrorCodes[] = {

{"INVALID_SOFTWARE_INTERRUPT", 0x07},

{"KMODE_EXCEPTION_NOT_HANDLED", 0x1E},

{"PAGE_FAULT_IN_NONPAGED_AREA", 0x50},

{"KERNEL_STACK_INPAGE_ERROR", 0x77},

{"KERNEL_DATA_INPAGE_ERROR", 0x7A},

};

Then we had a bunch of common error codes. Note that these are called

BUG_CHECK_CODE because “bug check” is the proper name for the BSoD, and in

fact, the kernel function that triggers them is called KeBugCheck. We needed

both the string name and the internal code, because the code will be shown in

the STOP: line.

HBITMAP RenderBSoD(void) {

HBITMAP hbmp;

HDC hdc;

HBRUSH hBrush = CreateSolidBrush(RGB(0, 0, 128));

RECT rect = {0, 0, 640, 480};

HFONT hFont;

char bsod[2048];

char buf[1024];

LPSTR lpName;

BUG_CHECK_CODE bcc;

DWORD dwAddress;

int i, k;

Now we have the RenderBSoD function, which returns an HBITMAP containing the

rendered image for the BSoD. Note that we hoist all the variable declarations to

the top of the function due to C89 limitations.

Most of these variables are self-explanatory or will soon be obvious. The

hBrush is the solid blue brush that will be used to paint the screen blue.

bsod is the final generated string that we initialize, since it’ll be used.

// Initialize RNG

k = Random() & 0xFF;

for (i = 0; i < k; ++i)

Random();

We then initialize the random number generator somewhat by taking a random byte and skipping ahead by that many numbers. This makes the output a bit more random.

hdc = CreateCompatibleDC(GetDC(hwnd));

hbmp = CreateCompatibleBitmap(GetDC(hwnd), 640, 480);

hFont = CreateFont(14, 8, 0, 0, FW_NORMAL, 0, 0, 0, ANSI_CHARSET, OUT_RASTER_PRECIS,

CLIP_DEFAULT_PRECIS, NONANTIALIASED_QUALITY, FF_MODERN, "Lucida Console");

We then create an HDC that’s compatible with our main window, whose handle

will be in hwnd when this function is called. The DC, or device context,

defines the attributes of the output device, which in this case is just a

screen, and contains some state for rendering parameters.

We then create a 640×480 bitmap that’s similarly compatible, onto which the BSoD will be rendered. Since 640×480 is the screen resolution that Windows falls back to when rendering the actual BSoD, this will make it look correct.

We then create the font. After some experimentation and comparison with a real

BSoD, I found that Lucida Console with height 14 and width 8 in GDI logical

units looked indistinguishable from the real one. It is very important to pass

NONANTIALIASED_QUALITY since there is no smoothing or ClearType™ on the BSoD,

and this ensures that the text looks as ugly as it does on the real screen.

lstrcpy(bsod, bsod1);

lpName = lpBadDrivers[Random() % ARRAY_SIZE(lpBadDrivers)];

bcc = lpErrorCodes[Random() % ARRAY_SIZE(lpErrorCodes)];

lstrcat(bsod, lpName);

lstrcat(bsod, bsod2);

lstrcat(bsod, bcc.name);

lstrcat(bsod, bsod3);

We populate bsod from the string fragments, inserting the driver name and the

error code string as necessary. The random number generator is used to pick a

random driver and code from the lists.

Note that we start the string with lstrcpy and then add onto it with

lstrcat. These are just the kernel32.dll versions of strcpy and strcat,

which we can’t use due to shunning the C library.

switch (Random() % 4) {

case 0:

wnsprintf(buf, ARRAY_SIZE(buf), bsod4, bcc.code, Random() | 1 << 31, Random() & 0xF,

Random() | 1 << 31, 0);

break;

case 1:

wnsprintf(buf, ARRAY_SIZE(buf), bsod4, bcc.code, Random() | 1 << 31, Random() | 1 << 31,

Random() & 0xF, Random() & 0xF);

break;

case 2:

wnsprintf(buf, ARRAY_SIZE(buf), bsod4, bcc.code, Random() | 1 << 31, 0, Random() & 0xF,

Random() & 0xF);

break;

default:

wnsprintf(buf, ARRAY_SIZE(buf), bsod4, bcc.code, Random() | 1 << 31, Random() | 1 << 31,

Random() | 1 << 31, Random() | 1 << 31);

break;

}

lstrcat(bsod, buf);

We generate a temporary string for the STOP: line from bsod4 with

wnsprintf (since we can’t use sprintf for aforementioned reasons), and then

append it. There are four different ways the bug check arguments could be

populated, since they aren’t always random numbers. If I cared more, I probably

could have made the numbers more realistic based on the error codes, but right

now, this just ensures that there are some small numbers, some big numbers, and

some zeroes in the parameters. We also guarantee the high bit is set on the

first parameter, which makes it look like a memory address in the upper half of

the address space, commonly used for kernel mode addresses.

lstrcat(bsod, bsod5);

dwAddress = Random() | 1 << 31;

wnsprintf(buf, ARRAY_SIZE(buf), bsod6, lpName, dwAddress, dwAddress & 0xFFFF0000, UnixTime());

lstrcat(bsod, buf);

Finally, we add the last two lines, including the module name again and some addresses. We just generate a random faulting address, and set the module base to the start of the 64 kiB block, and then plug in the Unix time.

At this point, bsod contains all the text to be shown.

SelectObject(hdc, hbmp);

SelectObject(hdc, hFont);

FillRect(hdc, &rect, hBrush);

SetBkColor(hdc, RGB(0, 0, 128));

SetTextColor(hdc, RGB(255, 255, 255));

DrawText(hdc, bsod, -1, &rect, 0);

We now load the bitmap and font into the HDC, then fill the entire bitmap with

the blue background brush. We then set the background and text colours, before

drawing the text.

DeleteDC(hdc);

DeleteObject(hBrush);

return hbmp;

We finally clean up the objects we’ve created, then return the bitmap created.

Entry point

Now we come to the startup sequence:

DWORD APIENTRY RawEntryPoint() {

MSG messages;

WNDCLASSEX wincl;

HMODULE user32;

We declare stack variables for processing window messages and a window class to

be registered, then an HMODULE to get a handle to user32.dll, whence we will

load ShutdownBlockReasonCreate and ShutdownBlockReasonDestroy for newer

versions of Windows.

hInst = (HINSTANCE) GetModuleHandle(NULL);

GenerateUUID(szDeskName);

ProtectProcess();

We initialize hInst. In 32- and 64-bit Windows, the HINSTANCE is just

the base address of the executable, which we obtain as above.

We then initialize szDeskName to be the secure desktop’s unique name, and

protect the process from being killed.

// Save the current sticky/toggle/filter key settings so they can be

// restored them later

SystemParametersInfo(SPI_GETSTICKYKEYS, sizeof(STICKYKEYS), &StartupStickyKeys, 0);

SystemParametersInfo(SPI_GETTOGGLEKEYS, sizeof(TOGGLEKEYS), &StartupToggleKeys, 0);

SystemParametersInfo(SPI_GETFILTERKEYS, sizeof(FILTERKEYS), &StartupFilterKeys, 0);

We save the initial state for the accessibility features too.

hOldDesk = GetThreadDesktop(GetCurrentThreadId());

hNewDesk = CreateDesktop(szDeskName, NULL, NULL, 0, GENERIC_ALL, NULL);

SetThreadDesktop(hNewDesk);

SwitchDesktop(hNewDesk);

We get the current desktop and then create a new one, then set the current thread to use that desktop, before switching the screen over to the new desktop.

If you have used Windows Vista or newer, you may remember the UAC prompt that dims the entire screen and heard it vaguely referred to as a “secure desktop”. This basically does exactly the same thing: we create a new desktop and switch to it. Since most normal GUI objects are desktop-scoped, including things like windows, menus, and most importantly, hooks, creating a new desktop isolates the window on it. In case of the secure desktop for UAC, no weird messages can be sent to windows on the new desktop, e.g. to simulate the “yes” button being clicked, and low-level keyboard hooks (which is how most keyloggers work) can’t be used to intercept the user’s keystrokes. This is how we defeat keyloggers.

The dimmed desktop for the UAC prompt is actually just a screenshot of the old desktop, dimmed, and rendered on a full screen window. Here, we don’t bother.

As a bonus, since no explorer is running on the secure desktop, it’s extra hard to find a way to break out of the BSoD.

#ifdef NOTASKMGR

if (RegCreateKeyEx(HKEY_CURRENT_USER,

"Software\\Microsoft\\Windows\\CurrentVersion\\Policies\\System", 0, NULL, 0,

KEY_SET_VALUE, NULL, &hSystemPolicy, NULL)) {

hSystemPolicy = NULL;

}

#endif

If we are disabling the task manager, we need to load up hSystemPolicy. We

open the registry key named, creating it if it doesn’t exist. If we should

somehow fail, we set hSystemPolicy to NULL, in which case

DisableTaskManager will fail gracefully.

wincl.hInstance = hInst;

wincl.lpszClassName = szClassName;

wincl.lpfnWndProc = WndProc;

wincl.style = CS_DBLCLKS;

wincl.cbSize = sizeof(WNDCLASSEX);

wincl.hIcon = LoadIcon(NULL, MAKEINTRESOURCE(1));

wincl.hIconSm = LoadIcon(NULL, MAKEINTRESOURCE(1));

wincl.hCursor = NULL;

wincl.lpszMenuName = NULL;

wincl.cbClsExtra = 0;

wincl.cbWndExtra = 0;

wincl.hbrBackground = (HBRUSH) GetStockObject(BLACK_BRUSH);

if (!RegisterClassEx(&wincl))

return 0;

We now populate the window class before registering this. This is just

boilerplate, except that we set the background as BLACK_BRUSH to simulate the

flash of black while the display mode changes, before the BSoD shows up.

user32 = GetModuleHandle("user32");

fShutdownBlockReasonCreate =

(LPFN_SHUTDOWNBLOCKREASONCREATE) GetProcAddress(user32, "ShutdownBlockReasonCreate");

fShutdownBlockReasonDestroy =

(LPFN_SHUTDOWNBLOCKREASONDESTROY) GetProcAddress(user32, "ShutdownBlockReasonDestroy");

We get an HMODULE to user32.dll and then load up ShutdownBlockReasonCreate

and ShutdownBlockReasonDestroy.

hhkKeyboard = SetWindowsHookEx(WH_KEYBOARD_LL, LowLevelKeyboardProc, hInst, 0);

hhkMouse = SetWindowsHookEx(WH_MOUSE_LL, LowLevelMouseProc, hInst, 0);

We also create low-level keyboard and mouse hooks to disable certain keys and all mouse movements.

hwnd = CreateWindowEx(0, szClassName, "Blue Screen of Death", WS_POPUP, CW_USEDEFAULT,

CW_USEDEFAULT, 640, 480, NULL, NULL, hInst, NULL);

ShowWindow(hwnd, SW_MAXIMIZE);

We create the window, and show it maximized.

hAccel = CreateAcceleratorTable(accel, ARRAY_SIZE(accel));

while (GetMessage(&messages, NULL, 0, 0) > 0) {

if (!TranslateAccelerator(hwnd, hAccel, &messages)) {

TranslateMessage(&messages);

DispatchMessage(&messages);

}

}

We now run the classic Window loop, except we construct the accelerator table

ahead of time and call TranslateAccelerator to interpret the keyboard

accelerators. If that function returns true, then the message should not be

processed further, per documentation, so we skip TranslateMessage and

DispatchMessage in that case.

ExitProcess(messages.wParam);

}

We close out RawEntryPoint with an ExitProcess call, since Windows by

default passes the return value to ExitThread and leaves all other threads in

the process running. Since threads may start for whatever reason these days, the

process might linger on indefinitely, and we ensure this isn’t the case via

ExitProcess.

The exit code is the wParam of the last message processed. The only way the

message loop can terminate is if it receives WM_QUIT, which is generated by

the PostQuitMessage function. Effectively, we exit the program with the value

passed to PostQuitMessage.

Low-level mouse hook

This is the low-level mouse hook, which just swallows all mouse events:

LRESULT CALLBACK LowLevelMouseProc(int nCode, WPARAM wParam, LPARAM lParam) {

if (nCode >= 0) {

return 1;

}

return CallNextHookEx(NULL, nCode, wParam, lParam);

}

Low-level keyboard hook

This is the low-level keyboard hook, which swallows all keys not used in any of our accelerators or would be required in the password dialogue:

LRESULT CALLBACK LowLevelKeyboardProc(int nCode, WPARAM wParam, LPARAM lParam) {

if (nCode >= 0) {

KBDLLHOOKSTRUCT *key = (KBDLLHOOKSTRUCT *) lParam;

switch (key->vkCode) {

case VK_LWIN:

case VK_RWIN:

case VK_TAB:

case VK_ESCAPE:

case VK_LBUTTON:

case VK_RBUTTON:

case VK_CANCEL:

case VK_MBUTTON:

case VK_CLEAR:

case VK_PAUSE:

case VK_CAPITAL:

case VK_KANA:

case VK_JUNJA:

case VK_FINAL:

case VK_HANJA:

case VK_NONCONVERT:

case VK_MODECHANGE:

case VK_ACCEPT:

case VK_END:

case VK_HOME:

case VK_LEFT:

case VK_UP:

case VK_RIGHT:

case VK_DOWN:

case VK_SELECT:

case VK_PRINT:

case VK_EXECUTE:

case VK_SNAPSHOT:

case VK_INSERT:

case VK_HELP:

case VK_APPS:

case VK_SLEEP:

case VK_NUMLOCK:

case VK_SCROLL:

case VK_PROCESSKEY:

case VK_PACKET:

case VK_ATTN:

return 1;

}

}

return CallNextHookEx(NULL, nCode, wParam, lParam);

}

Window procedure

The window procedure is the event handler for the window, effectively. It starts like this:

LRESULT CALLBACK WndProc(HWND hwnd, UINT message, WPARAM wParam, LPARAM lParam) {

int i;

switch (message) {

We define a loop variable for use later due to C89 and use a switch statement

to match on the message ID.

case WM_CREATE:

scwnd = CreateWindowEx(0, "STATIC", "", SS_BITMAP | WS_CHILD | WS_VISIBLE, 0, 0, 640, 480,

hwnd, (HMENU) -1, NULL, NULL);

#ifndef NOAUTOKILL

SetTimer(hwnd, TM_AUTOKILL, AUTOKILL_TIMEOUT, NULL);

#endif

SetTimer(hwnd, TM_DISPLAY, DISPLAY_DELAY, NULL);

SetTimer(hwnd, TM_FORCEDESK, FORCE_INTERVAL, NULL);

SetCursor(NULL);

if (fShutdownBlockReasonCreate)

fShutdownBlockReasonCreate(hwnd, L"You can't shutdown with a BSoD running.");

// Force to front

SetWindowPos(hwnd, HWND_TOPMOST, 0, 0, 0, 0,

SWP_ASYNCWINDOWPOS | SWP_NOACTIVATE | SWP_NOMOVE | SWP_NOSIZE);

SetForegroundWindow(hwnd);

LockSetForegroundWindow(1);

AllowAccessibilityShortcutKeys(FALSE);

#ifdef NOTASKMGR

DisableTaskManager();

#endif

break;

In our WM_CREATE handler, which is called upon window creation, we create a

static control to display our blue screen bitmap.

We also set a bunch of timers:

- If

NOAUTOKILLis not defined, then we set up a timer to signal the program to exit, which is invaluable for debugging; - We set a timer to display the BSoD after initially blacking out the screen; and

- We set a timer to forcefully switch the desktop to our secure desktop, in case someone switches it back somehow.

We also hide the cursor, since a mouse cursor on the BSoD gives the game away pretty quickly.

We then create a shutdown blocking reason. Note that

fShutdownBlockReasonCreate takes exclusively Unicode strings, so we needed to

use a const wchar_t * literal with the L prefix on the string.

We then move the window to the front through SetWindowPos, with HWND_TOPMOST

to guarantee the window shows up above all normal windows. We set it to the

foreground window and prevent any other process from taking over with

LockSetForegroundWindow.

Finally, we disable accessibility shortcuts and the task manager.

case WM_SHOWWINDOW:

return 0;

We ignore all WM_SHOWWINDOW by returning 0 immediately, skipping the

processing in DefWindowProc, which may hide the current window.

case WM_TIMER:

switch (wParam) {

We now handle the timers.

case TM_DISPLAY: {

RECT rectClient;

KillTimer(hwnd, TM_DISPLAY);

SendMessage(scwnd, STM_SETIMAGE, (WPARAM) IMAGE_BITMAP, (LPARAM) RenderBSoD());

GetClientRect(hwnd, &rectClient);

SetWindowPos(scwnd, 0, 0, 0, rectClient.right, rectClient.bottom,

SWP_NOMOVE | SWP_NOZORDER | SWP_NOACTIVATE);

InvalidateRect(hwnd, NULL, TRUE);

break;

}

For TM_DISPLAY, we stop the timer from firing again, then render the BSoD and

set it as the bitmap shown by the static control. We then make the static

control cover the whole screen, before forcing the whole window to repaint.

#ifndef NOAUTOKILL

case TM_AUTOKILL:

KillTimer(hwnd, TM_AUTOKILL);

DestroyWindow(hwnd);

break;

#endif

If the safety timeout triggers, we stop the timer from triggering again, and

then call DestroyWindow to tear everything down.

case TM_FORCEDESK:

SwitchDesktop(hNewDesk);

break;

}

break;

This is pretty self-explanatory.

case WM_DESTROY:

if (fShutdownBlockReasonDestroy)

fShutdownBlockReasonDestroy(hwnd);

UnhookWindowsHookEx(hhkKeyboard);

UnhookWindowsHookEx(hhkMouse);

DestroyAcceleratorTable(hAccel);

LockSetForegroundWindow(0);

AllowAccessibilityShortcutKeys(TRUE);

SetThreadDesktop(hOldDesk);

SwitchDesktop(hOldDesk);

CloseDesktop(hNewDesk);

#ifdef NOTASKMGR

EnableTaskManager();

#endif

PostQuitMessage(0);

break;

Upon receiving WM_DESTROY, we perform cleanup:

- removing the shutdown block on newer Windows;

- unhook the mouse and keyboard;

- clean up the acclerator table;

- unlock the foreground window;

- reset the accessibility shortcuts;

- switch the desktop back;

- clean up the secure desktop;

- re-enable the task manager if we disabled it; and

- exit the message loop and the program.

case WM_CLOSE:

switch (DialogBox(hInst, MAKEINTRESOURCE(32), hwnd, DlgProc)) {

case 1:

DestroyWindow(hwnd);

break;

case 2:

hdlg = HDLG_MSGBOX;

MessageBox(hwnd,

"You got the password wrong!\n"

"Good luck guessing!",

"Error!", MB_ICONERROR);

hdlg = NULL;

break;

default:

hdlg = HDLG_MSGBOX;

MessageBox(hwnd,

"You just abandoned the perfect chance to exit!\n"

"Good luck trying!",

"Error!", MB_ICONERROR);

hdlg = NULL;

}

break;

Upon receiving WM_CLOSE, which means someone is trying to close the window, we

invoke DialogBox to create a dialogue from our resource template and use

DlgProc as the dialogue procedure.

If the dialogue procedure returns 1, signalling the password is correct, we

destroy the window. If it returns 2, we show a taunting message for an

incorrect password, and any other value means the dialogue box was closed, and

we show a different taunting message.

For reference, the dialogue template is in bsod.rc and looks like:

#include <winuser.h>

#define IDC_EDIT1 1024

#define IDC_STATIC -1

32 DIALOGEX 0, 0, 256, 73

STYLE DS_SETFONT | DS_MODALFRAME | DS_FIXEDSYS | WS_POPUP | WS_CAPTION | WS_SYSMENU

CAPTION "Dialog"

FONT 8, "MS Shell Dlg", 400, 0, 0x1

BEGIN

EDITTEXT IDC_EDIT1,47,33,201,14,ES_AUTOHSCROLL | ES_PASSWORD

LTEXT "It seems like you are trying to exit a Blue Screen of Death, which is impossible. But if you are a hacker and knows the password, you might be able to.",IDC_STATIC,7,7,240,27

LTEXT "Password:",IDC_STATIC,7,36,38,8,0,WS_EX_TRANSPARENT

PUSHBUTTON "&OK",IDOK,145,49,50,14

PUSHBUTTON "&Cancel",IDCANCEL,198,49,50,14

END

Back to the window procedure…

case WM_KEYDOWN:

return 0;

We skip the weird WM_KEYDOWN handling for F10 in DefWindowProc by

doing this.

case WM_COMMAND:

case WM_SYSCOMMAND:

if (HIWORD(wParam) == 1) {

if (LOWORD(wParam) == 0xDEAD) {

for (i = 0; i < ARRAY_SIZE(bAccel); ++i)

if (!bAccel[i])

return 0;

SendMessage(hwnd, WM_CLOSE, 0, 0);

} else if ((LOWORD(wParam) & 0xFF00) == 0xBE00) {

int index = LOWORD(wParam) & 0xFF;

if (index < ARRAY_SIZE(bAccel))

bAccel[index] = TRUE;

}

}

break;

This handles the keyboard accelerators. Whether WM_COMMAND or WM_SYSCOMMAND

is generated is kinda complex and it doesn’t really matter here, so we just

treat them the same. If HIWORD(wParam) == 1, then it’s an accelerator key, and

LOWORD(wParam) is what we put into the accelerator table above:

- If it’s

0xDEADand all other accelerators have been pressed, we sendWM_CLOSE, initiating the procedure above to show the password prompt. - If it’s

0xBExxand the low-order byte is a valid index, we mark it as pressed.

case WM_QUERYENDSESSION:

return 0;

This tells Windows XP that the user shouldn’t be allowed to log out. Typically, this is done in response to unsaved documents, but we are abusing it to prevent logouts without the password.

Perhaps due to applications just returning 0 for all messages instead of calling

DefWindowProc, or otherwise abusing WM_QUERYENDSESSION, Windows Vista

introduced the whole ShutdownBlockReasonCreate thing…

case WM_ENFORCE_FOCUS:

if (GetForegroundWindow() != hdlg) {

if (hdlg && hdlg != HDLG_MSGBOX) {

SetFocus(hdlg);

SetForegroundWindow(hdlg);

} else if (!hdlg) {

SetFocus(hwnd);

SetForegroundWindow(hwnd);

SetWindowPos(hwnd, HWND_TOPMOST, 0, 0, 0, 0, SWP_NOMOVE | SWP_NOSIZE);

}

}

SetCursor(NULL);

ShowWindow(hwnd, SW_SHOWMAXIMIZED);

break;

This is a custom window message that we use to reset the foreground window,

should we somehow stop being it. We set the focus on hdlg if it exists,

otherwise the main window, which we ensure is topmost. However, if we are

showing a message box, we don’t change the focus.

We also hide the cursor and maximize the window.

case WM_ACTIVATE:

if (LOWORD(wParam) != WA_INACTIVE)

break;

if (!HIWORD(wParam))

break;

case WM_NCACTIVATE:

case WM_KILLFOCUS:

PostMessage(hwnd, WM_ENFORCE_FOCUS, 0, 0);

return 1;

If we detect the window has been deactivated somehow or lost focus, we post the

message WM_ENFORCE_FOCUS to be handled the next time the message loop runs.

case WM_SIZE:

if (wParam != SIZE_MAXIMIZED)

ShowWindow(hwnd, SW_SHOWMAXIMIZED);

break;

If we receive a WM_SIZE telling us we are no longer maximized, undo that.

default:

return DefWindowProc(hwnd, message, wParam, lParam);

}

return 0;

}

And we wrap up the window procedure by calling DefWindowProc for all other

messages, and return 0 if we’ve handled any other message that didn’t return

early.

Dialogue procedure

And finally, we have a dialogue procedure for the password dialogue:

INT_PTR CALLBACK DlgProc(HWND hWndDlg, UINT msg, WPARAM wParam, LPARAM lParam) {

UNREFERENCED_PARAMETER(lParam);

switch (msg) {

This is how it starts. We use the UNREFERENCED_PARAMETER macro to avoid a

warning being generated by Microsoft’s compilers at /W4 level of warnings,

since we never touch lParam.

We then handle each dialogue message, which acts like window messages…

case WM_INITDIALOG:

hdlg = hWndDlg;

break;

Upon WM_INITDIALOG, which is sent when the dialogue is initialized, we set

hdlg to save the window handle.

case WM_COMMAND:

switch (wParam) {

Upon WM_COMMAND, which happens when a button is clicked, we switch on

wParam, which contains the ID of the button being clicked.

case IDOK: {

DWORD dwLength, i;

TCHAR szPassword[PASSWORD_LENGTH + 1];

dwLength = GetDlgItemText(hWndDlg, IDC_EDIT1, szPassword, PASSWORD_LENGTH + 1);

if (dwLength != PASSWORD_LENGTH) {

EndDialog(hWndDlg, 2);

hdlg = NULL;

break;

}

for (i = 0; i < PASSWORD_LENGTH; ++i)

szPassword[i] ^= 37;

EndDialog(hWndDlg, lstrcmp(szPassword, szRealPassword) ? 2 : 1);

hdlg = NULL;

break;

IDOK is the default ID for the OK button in a dialogue box, and we use

GetDlgItemText to get the text for the dialogue item with IDC_EDIT1, which

is our password edit control. We load the bytes into szPassword, which is just

enough to fit the correct password.

If GetDlgItemText returns the wrong length, we end the dialogue with code 2,

meaning incorrect password.

Then, we XOR every byte in the password with 37 to encode it, before using

lstrcmp to compare it with the real password. lstrcmp is kernel32.dll’s

version of strcmp, which again we can’t use due to shunning the C library.

We end the dialogue with code 1 if it’s correct, otherwise 2.

case IDCANCEL:

EndDialog(hWndDlg, 0);

hdlg = NULL;

break;

}

break;

We end the dialogue with 0 otherwise, to signal the dialogue was cancelled.

default:

return FALSE;

}

return TRUE;

}

And finally, we return TRUE if we handled the message, and FALSE if we

didn’t to trigger the default behaviour. This is where dialogue procedures

differ from window ones, and honestly, I think the DefWindowProc approach is

more flexible.

Conclusion

And that’s the end of this little program. I hope you learned a bit about programming in C or writing Windows applications, especially a funky one like this.

Notes

-

Yes, this predated the Windows XP end-of-support date of April 8, 2014, but the school just continued running Windows XP anyway. It wasn’t until 2015 that all the computers were upgraded to Windows 7, and boy was it slow on those ancient Pentium Ds, which were around 10 years old by that time. It probably explained why they held onto Windows XP as long as possible.

For those who are too young to remember, that was a reasonably innovative era in PC hardware, so 10-year-old computers were a lot more unusable compared to 2026. ↩

-

I obviously knew which computer was the fastest in every lab and made sure to secure it for my own use whenever possible. They were still super slow, especially in the Windows 7 era, but better than being stuck with something even worse. ↩

-

Yes, Microsoft used Unix time on the BSoD. It is perhaps somewhat ironic, but they did make Xenix at one point… ↩

-

Yes, it was an ancient toolchain, surprisingly lightweight and popular, even a decade and half after its release. Pretty good for a toolchain as old as me. ↩

-

For those of you wondering how I got VC6 to run on Jenkins, the answer is Wine, because I am not specifically deploying a Windows server to run VC6. My debloated VC6 package just ran perfectly fine. ↩

-

For those too young to remember, AMD’s graphics card division was acquired from ATI. ↩